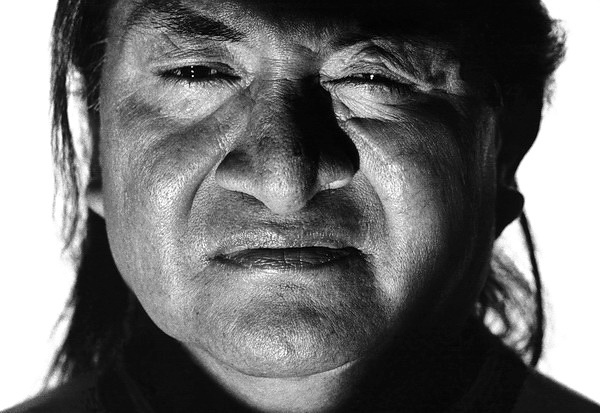

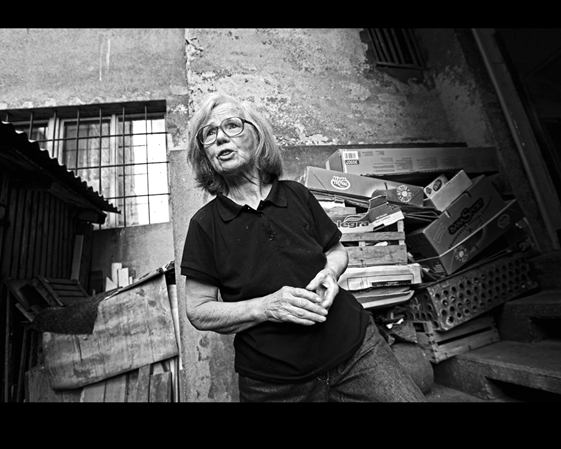

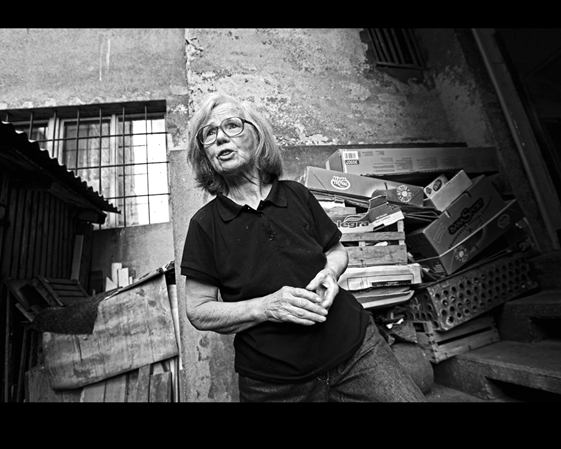

Daniel Kaifer, Photographer, Czech Republic

Daniel Kaifer’s life is closely tied into the small town Horská Kvilda, where he has lived with his family for seven years now. His photographs pay tribute to this place and its inhabitants and depict an atmosphere you could not find in any larger town. Come read an interview with a man who humbly claims that he‘s just a kind of sleepy bear that withdrew into the mountains.

When did you first get acquainted with the medium called photography? And how has your relationship with photography developed? Are you an amateur or a semiprofessional?

I became acquainted with photography at university, as a hobby. I hitchhiked through Europe and wanted to have a way to keep my memories. And so I bought my first camera at Mr. Škoda in Prague. It was an old PENTAX program A with a 35-105 mm lens. This configuration made it rather a brick, not very suitable for traveling but reliable. I later enlarged all the images to 24×36 mm prints, glued them to cardboard and hung them on the wall in my room on campus. It had nothing to do with quality and real photography. Of course later my relationship with photography developed further and changed but the prehistory of my relationship with photography began in this way.

Whether I’m a professional? Ummm, Yes, I am. I see the difference between an amateur and a professional in that a professional is always and under any circumstances able to create a valuable image crafted with care, which has a high quality technically and also contains something extra – a message, which you then carry yourself as the author to the viewer. You are able to speak to the viewers and easily pass on your testimony to them. An amateur sometimes succeeds in this and sometimes not. Although the craft is mastered (perhaps thanks to new technology), the important aspect is missing – the testimony. I see the fundamental difference here. It’s secondary whether you get paid for photography or whether you do it due to some internal overpressure and a need to express yourself.

An experienced cliché is that a professional is someone who has a well-known name and earns money with photography, perhaps even a lot of money. An amateur does it for his own pleasure and is not very good at it. I believe that this is indeed a cliché. It’s only marketing and the ability to sell photography as such. In my view, the so-called professionals and amateurs often overlap. In both directions.

I can perhaps back up my claim that I’m a professional with the fact that this year I obtained a QEP certificate, which is being awarded by the Federation of European Professional Photographers. But is it important? Why do these two pigeon-holes exist? Isn’t this question only about one’s own ego?

What does photography give you personally, what meaning do you find in it?

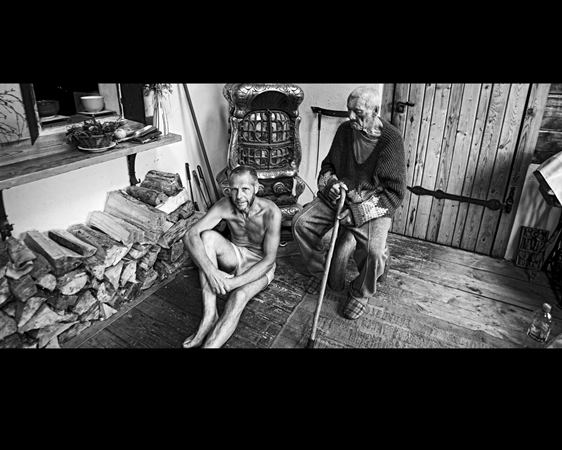

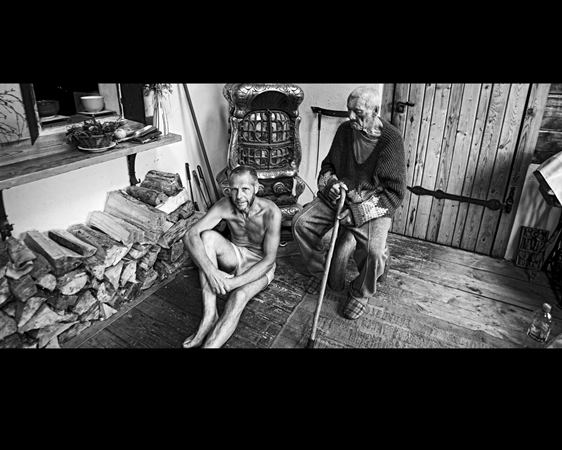

Photography is an amazing adventure. In photography, I primarily look for the wonderful moment of a story being born, of the most common story, which is everywhere around us. This moment cannot be thought up in advance, this fleeting instant cannot be planned, you cannot force it out, you can only and only get them from life. It’s a gift. It’s a journey of searching through life and finding, discovering. It’s not possible to create the scene like in the theater, I’m not a director. I’m merely a spectator drawn into the story. When photographing a documentary I encounter many people and stories. In order for photography to convey testimonies, it must be natural without calculation, without manipulating with the “actors” on the stage. In my opinion, such stories can be photographed only with great honesty and humility towards the people I try to capture. This all is not possible without me getting to know everyone, every photographed person. And some images take up to five years to be created. While I photograph, nice relationships, sometimes friendships, are formed. The photograph is in these cases only a sort of a cherry on top, a bonus, a dessert, in which everything joins into one. In such moments, the photograph is not even important, everything else is secondary and it lives its own life, on which I have little influence any more. And I have an opportunity to pass all of this over to the viewer as the author, well isn’t it beautiful to be in the world for this?

The second thing is the opportunity for the freest outlook on life. There is no force, which can prevent you looking at this world freely. Books can be burned, mouths can be shut. But it is always possible to see this world freely. Even without a camera. The camera is only a tool, an instrument, an intermediary. Of course, we can be affected by the time, environment, in which we live, the people, with whom we live, but no one can ever take this freedom away from you.

What is your job, what are your hobbies and where do you live with your family?

That’s probably not very interesting…, originally my profession was a construction engineer (heating, boiler rooms, gas lines, power engineering and so forth). At the moment it’s kind of half and half, sometimes more photography, sometimes more engineering. For seven years now, I’ve lived with my family in the middle of the national park in Šumava in Horská Kvilda, beautiful nature, a healthy environment for children, peace, a lot of snow, temperatures of up to -42 °C. The price for it is that one must make money for bare survival in several ways, not only with photography, not only with engineering. The hobbies are obvious – cross-country skiing and mountains, poetry, music…, but that probably isn’t interesting.

Do you think that it is possible to earn a living with the sale of documentary photographs in this country at this time?

I cannot answer this question. If I speak for myself, I must say that it’s not possible. For a long time I have tried to find a way to earn a living with documentary photography in a place that has 50 permanent inhabitants. To tell the truth, I have not accomplished that and am not able to do that. I ascribe this to two factors. First, I am not a businessman. Someone who would stand in front of the buyer and sell his goods as the most perfect thing in the world. I would more likely draw the buyer’s attention to the faults I see in my work. This may be sincere but it’s not a business policy. I consider this my own failure because a professional photographer should be good at the business part of the craft as well. It’s true that photographs should be sold by galleries and gallerists but this photography market unfortunately does not work here. All the same, this sentence is not an excuse, it’s a mere grumbling about myself.

The second factor is that today, the common spectator is overwhelmed with the slush of the postmodern time and technical possibilities he cannot fully make use of. Photography becomes only a bare message, information, decoration. The testimony disappears. There is no time to search, it’s necessary to sell and subordinate the photograph – that is, the message – to this goal. I cannot judge whether this is good or bad but the art of reading photography is definitely disappearing. What actually is a good photograph today? Meaningless colored enlargements or small pieces of paper hidden somewhere in a drawer? Who today still reads poetry? Who today is still able to read photography? Why buy a documentary photograph for hundreds of Euros? And even hang in at home as a decoration?

And so I have come to the attitude where I believe that if my work is good and of high quality, it will find its way to the viewer alone and even sell itself. And if isn’t good? It has no right for any further life and my effort is only another vanity in this world. But I enjoy it. And if my photographs are sold? Is that an important question??

Where did you first come across the project Week of Life and how did you feel about it?

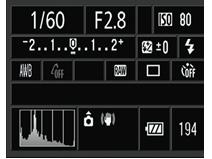

I learned about the Week of Life project from Mr. Jiří Heller. Take nine photographs in a day seven times in a row. It was on a Monday evening, I was moving and completely remodeling my study and in addition, I had to submit some work. Nine photographs a day? Whole week? At first I didn’t want to go ahead with it at all, I had no time, I had better things to do. There are days when stories just pour into your life, one after another, and then comes a day, which you spend laying in bed and all you encounter during the day are the boards on the ceiling. And we are back to the first question, who is a professional and who is an amateur. A professional must be able to photograph even the ceiling boards. Nine quality photographs a day with a story about where I live, whom I meet, what is its story? That’s a challenge though! And why not right now, when else… Week of Life was a challenge for me, a challenge in a field of photography, which is very close and dear to me. I hope that I have not let the viewers down and I hope that I have communicated my story to at least one of them.

Do you think that this type of project could in any way help society or be in any way useful to an individual?

I’ve been going through old photographs of Šumava and the most ordinary and sometimes even poor quality photographs of people, places, gain incredible immense value after the decades. It’s a view into one’s own past, on which I can reflect as a spectator. I can discover that I’m free. I can treat it in a way I deem the best. The one who knows one’s past, one’s story, has a chance to learn about oneself. I think that Week of Life is an enormous message to the future. This is who we are and this is how we live. This is more important that the ego of each individual author, more important than the technical aspect of the matter. The ability to learn about yourself is the project’s contribution. I would wish the project not to slip into another ‘web photo gallery’ and maintain its high standard. That’s a very difficult and tough task in today’s world!

Yes, you are right, the internet is full of slush and it is not easy to maintain quality, especially in the battle for advertisers. What is your view of the internet in general and in relation to photography? And in which direction do you think will it develop?

In the face of all negatives, which are being written about the internet today and despite all dangers, which it holds, I have to answer that the internet is a living organism, which can connect individuals on this Earth. It’s similar as with fire, a good servant but a bad master. I like fire, I like its warmth, but I fear its power, which I’m unable to comprehend and fully control. It is similar with the internet. It is amazing that the internet enables me to share the stories of other people and not only that. I can communicate with them, I can live their life with them at a distance and it extends my freedom. Freedom that ends beyond the border of my physical existence. I can continue to learn new things. On the other hand I see a danger in alienation from one’s own surroundings, one’s significant others. I am a little schizophrenic from the two worlds – the physical and virtual. I have no idea how the internet will develop further, but I think that we are in a developmental stage comparable to puberty or, using technical terminology, at the level of the steam engine. There are amazing things ahead of us – machines that fly and land on the moon – to wit, things we can’t even imagine today.

It’s similar in terms of photography. On the one hand, I heard recently that František Drtikol does not have a website and is not on facebook and thus it’s as if he didn’t exist. Martin Luther also doesn’t have a website and yet his legacy will live inside me until the end of my days. Then there are internet projects such as lens.blogs.nytimes.com of the New York Times, which fascinate me and which affect my life every day. And I believe that thanks to digitalization, the journey of photography was given immense and unsuspected possibilities but … The journey of photography has not become easier, rather the contrary. It is more difficult, photography as such is subject to new questions, new challenges. We must firstly accept that digitalization is a fact and secondly realize what do we really want to convey? Whom do we want to convey it to? How much do we want to convey it? How far can we go? Have we tried all possible means? Where are the limits of these questions? And what are the off-limits where one should not or must not go? You are also right in your question that the battle for advertisers is getting more and more difficult. Which advertiser is able to recognize a photograph of truly high quality in the infinite number that there is? Is good photography yours, or perhaps mine? What if we are both mistaken? And if we look around, the situation in our Czech playground is very sad, isn’t it? And we’re only talking about commercial sales of photographs. I have to repeat – the journey of photography has not become easier – it is becoming increasingly difficult with an inverse proportion. We face so many challenges. And technology keeps on getting ahead of us. I think it will all end up that in the future, recording reality will change to such an extent under the influence of technology that photography will be free, not marginal but free – only one of the ways to convey testimony. For instance, holographic 3D records of reality will exist, which will include aroma and emotional tracks and which will be captured with devices of the size of current compact cameras… and will be distributed on a mass scale. Or a small MATRIX will come. But it will not kill photography, on the contrary, it will become freer. I am looking forward to this time because I will be freer, technology will untie my hands, technology will enable to pass my testimony to as many people possible. It is technology that kills the slush we flounder through today. I have hope for this. But photography can be liberated only by photographers and their stories.

The last question – where do you see your future as a photographer? How will your path develop or how would you like your path to develop?

I would like to complete my two semi-finished projects – portraits of old women and a poetic documentary about people from Šumava. For two years I have been publishing a poetic irregular Friday piece Hlas Divočiny (Voice of the Wild). I choose the best photograph of the whole week, I write a text for it, which was going through my head while I was taking it and each Friday I send the whole thing to my readers. It’s sort of a gift, which I’d received, so why not send it forward as a gift. I would like to continue doing this for a few years.

I don’t think that my photographic career will change in any fundamental way. Perhaps I will be discovered and will exhibit in the whole Western hemisphere. Frankly speaking, there are many photographers like me and I certainly don’t belong among the best. I am just a kind of a sleepy bear that withdrew into the mountains. I wander through the country among people. However, it would be insincere to say that it does not please me when someone likes my work, when it appeals to someone, makes them think. It would be insincere to say that I don’t have to come down from the mountains to gather new strength in the valley.

How would I like for everything to develop? I would like to undertake a journey through Spain, three to four weeks, to meet new people, new stories and try to pass it on through photography. It would be nice if my photographs were sold more, for me to be able to maintain a professional standard of equipment and not have to finance it from the family budget. It would be nice. But who wouldn’t want this, right?

Just to walk through the land, step by step, not hurry anywhere, have everything I want, all mountains, trees and my own sins. Then I would be very happy and wealthy man.

Weeks of Daniel Kaifer